Introduction to Propaganda and the Blitz

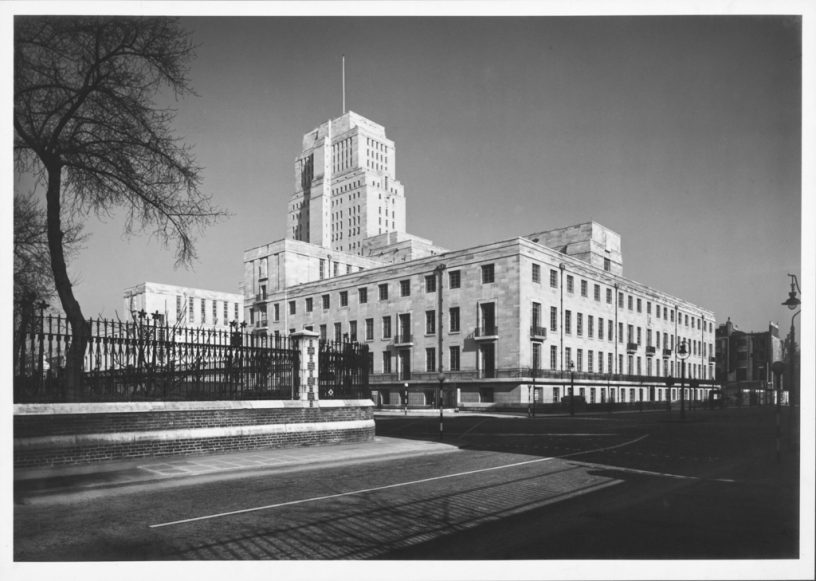

Starting in September 1940 and lasting until early summer 1941, The Blitz was a period in World War II in which Britain, and in particular London, sustained heavy bombings by Nazi Germany. London itself was attacked more than 70 times causing a considerable number of civilian casualties. For the first few months of The Blitz, the British government and the Ministry of Information (Britain’s propaganda headquarters during the war) had two main goals: 1) Boost morale in Britain by way of a cultural solidarity campaign and 2) Present a positive image of Britain abroad, specifically to the US, in order to obtain American aid. As Cull writes:

The Blitz on London shifted the burden of the war onto the civilian population. This created new publicity needs. The Blitz was a human story and required a sympathetic human eye to capture it. Britain’s need for its resident American journalists had never been greater. The working relationships between the Americans and British propagandists became a key factor in securing aid and hence in ensuring Britain’s survival. (Cull 98-99)

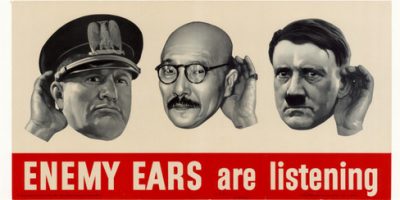

Cull’s main point, here, and throughout the chapter you had to read for today, is that propagandists and journalists from both Britain and the US worked together to create a new cultural identity for Britain as part of a larger publicity campaign. This included pamphlets and posters distributed in Britain and the US, radio broadcasts like those of famous playwright J.B. Priestly, novelist George Orwell, and renowned American journalist Edward R. Murrow, and a slew of films created on both sides of the Atlantic by famous directors such as Alfred Hitchcock and the German-Expressionist turned Hollywood director, Fritz Lang. Regardless of which medium was used, however, certain messages about Britain were reiterated time and time again. So today, we’re going to take a look at six of the defining elements / narratives of British identity during The Blitz, much of which has become part of our shared cultural memory (for example, the stoicism of Britain in the face of tragedy has persisted).

“Business as Usual”

“Business as Usual” was one of the main themes of Britain’s publicity campaign. At the heart of this campaign was the narrative that despite the bombings, Britons, and in particular Londoners, carried on with their lives as if nothing out of the ordinary were happening. By doing so, the British propagandists hoped to convince the British public of their duty to “keep calm and carry on.” They also hoped to show Americans a Britain that was resilient and thereby worthy of aid. In the chapter you read for today, Cull emphasizes the international nature of this image creation:

Radio coverage of the Blitz was an Anglo American co-production. The BBC and CBS teamed up to produce a new feature, ‘London Carries On,’ and to bring the sounds of Britain at war into American homes. It became impossible to say where CBS or NBC producers began and the BBC and MoI work stopped. (Cull 106)

In this clip, the pub owner and his wife dust off the curtains that have fallen to the ground and open the pub for business despite the fact that not 5-minutes before, a bomb destroyed the front wall of the building. The “Business as Usual” message is further underscored by the fact that the owner requests that patrons still use the door to his pub despite the gaping hole in the wall. Even cats “carry on” as usual during The Blitz, as seen through the delivery of a litter of kittens during the bombing itself. Moreover, at the end of the scene an agitator for wartime surrender is kicked out of the pub, while a local civilian reflects proudly on his wartime position as a firefighter and his being drafted as a soldier, sending the message that this is a war to be proud of.

Home Front and War Front Indistinguishable AND “People’s War”

Another significant cultural image produced by films of the time is that the home front and the war front are no longer two separate entities like they were for the British during World War I. The Nazis have brought the war to British soil. This is of course evident in the clip form Unpublished Story where we see the physical evidence of the bombing’s destruction.

Because the war was brought to Britain, the government and the Ministry of Information needed British civilians—men and women, old and young—to think of themselves as soldiers. Therefore, the phrase “People’s War” became a central image in Britain’s rebranding. Cull writes about this phrase being central to Britain’s reputation abroad, particularly in messages to the US, which still thought of Britain as being in want of democratic qualities.

By the early summer of 1940, the idea of national and social regeneration had become fundamental to some British and most American commentaries on the war. The American correspondents seemed to accept that Britain had cast off its old ways and was now fighting a “People’s War.” The war news itself supported this. Little holiday steamers had plucked the British Army from French beaches [this is the glamorization of the Dunkirk operation]; old men had rallied to form the Home Guard; and all across the country, the ordinary folk of England were moving into the front lines. The common experience of suffering and endurance during the Blitz confirmed this. (Cull 99)

The phrase the “Peoples War” conjured up images of rich and poor fighting together. War had made Britain egalitarian. And by shedding its imperialist image, the British government hoped to gain the support of the American people. And the message was obviously received by the US. Even in 1944, Hollywood filmmakers like Fritz Lang were presenting an image of the Second World War as a universal conflict. In this adaptation of a 1942 Graeme Greene novel, Lang’s protagonist finds himself caught up in an international spy ring. The war has come to him and he alone can stop Britain’s tactical battle plans from leaving British soil. In this early scene of the film pay particular attention to the chase. The British landscape looks like No Man’s Land from WWI (suggesting point #2) and the protagonist’s pursuit of the spy suggests that each Briton has a responsibility to fight.

Religion (Britain Christian / Germany Pagan)

In order to create a unified image of British culture, however, propagandists also relied on the promotion of false dichotomies between Britain and Germany. One main division that found its way into multiple movies was religion. Britain is frequently depicted as a historically Christian culture and Germany, despite its role in the Protestant Reformation, is depicted as pagan. In fact, the BBC spent numerous hours on religious programming during the war that also had a political slant. Once again, the goal was not only unifying the British people through a shared Christian culture, but also creating further ties between Britain and America. Britain essentially argued that the US should join the side of the British because of a shared Christian identity / history. The war itself was even spoken of as a religious conflict and Americans ate this up. Cull notes that the American journalist Dorothy Thompson spoke of Britain as experiencing a religious rebirth:

Dunkirk […] had been the moment of death and resurrection, when “one Britain lost the war” and “another Britain was born.” The evacuation had been a miracle of Biblical proportions, conducted by civilians “from every village and hamlet on the coast of England.” (Cull 100)

In 1942, this image made its way onto the big screen in MGM’s Mrs. Miniver, another adaptation of a British novel. In fact, not only does the stationmaster, Mr. Ballard, discuss the war as a religious struggle but Dunkirk is also the focus. Mrs. Miniver’s husband (who is an architect by trade) has gone as a civilian to participate in the evacuation, furthering the image of a “People’s War.”

Notice also in this clip that the image of Britain as “carrying on” with “Business as Usual” despite the war is depicted through Mr. Ballard’s insistence that the annual Rose Show will take place regardless of the bombings. And, he proves to be right.

Personality (Britain = Rational / Germany = Emotional)

This religious dichotomy was also played up in non-religious terms. Despite the bombings, Britons were depicted as calm, rational, and caring, even of their enemies. Germans on the other hand were depicted as animalistic and emotional brutes. In the scene that follows the last clip, Mrs. Miniver stumbles upon a German pilot who has lost his way after ejecting from his crashing airplane. He is injured but holds Mrs. Miniver hostage for food and clothing. Notice in this next clip how Mrs. Miniver’s empathy and understanding goes above and beyond, as does her ability to stay calm despite the immediate threat to her life.

Mrs. Miniver’s struggle with the Nazi pilot also plays up the larger cultural representation of the war as a “People’s War.” This struggle in her home on British soil is shown to be as significant in winning the war as the evacuation of Dunkirk where her husband is currently participating in the war effort. In fact, this battle is even more significant that the British areal dogfights, in which her son partakes, but is given considerably less screen time.

Class Lines Dissolving

I’m going to show one last clip from Mrs. Miniver that emphasizes many of the propaganda narratives that I’ve spoken about today including Britain’s Christianity, the “People’s War,” “Business as Usual,” and a home front battle. In this final scene of the film, Mrs. Miniver and her family are in a bombed church mourning the loss of numerous villagers. But this scene also pushes the egalitarianism of the war even further, suggesting that British class lines are dissolving. This is best seen through Vin Miniver’s actions, as he (a middle-class war pilot) comforts Lady Beldon (the local aristocrat).

I think the final moments of this film sum up the American interpretation of Britain’s new cultural identity as a resilient Christian people who are not afraid to fight.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.